Unfortunately, the telegraph was quickly phased out for more modern equipment. Technology was heavy, expensive, and required delicate care to remain working. Wires would be subject to gunfire and bombs, causing them to constantly require repairs. It wasn’t uncommon for a signaller to have to fix 40 cables per day. Wireless transmissions became a priority during the Second World War.

|

HOMING PIGEONS were a large part of ensuring communication between the front and rear lines. With all the chaos happening on the ground, pigeons used to offer immense help by carrying messages through the sky. Although shells still riddled their paths, pigeons made for a far smaller target. Harming a pigeon in any way was considered a great offense, and could result in a fine or even imprisonment. These birds were extensively cared for. They would be groomed, protected from gas fumes, transported in mobile carrier vehicles, and brought into the dugouts during attacks. In most cases, they were cared for better than front line horses. A common practice when sending pigeons was to send two with the same message to ensure its arrival. During Operation Jubilee, one pigeon fondly nicknamed “Beachcomber” by the troops delivered the first news of the Dieppe Raid in France 1942. He carried a small container with the message inside attached to his leg, and he set off alone. This communication proved to be vital, as allied commanders had lost sight of the troops on the beaches. Beachcomber was awarded a Dickin Medal in 1944 for delivering such an important message under hazardous conditions. He was one of the only three animals who received the award during the Second World War. SEMAPHORE FLAG SIGNALS were handheld beacons used for daytime signalling during the Great War. The flags were created in bright colours to ensure visibility over great distances. They featured two colours split diagonally through the middle of the flag. A signaller would hold one flag in each hand and move them in specific positions to represent numbers and letters. A team of about ten signallers could transfer a message across a 5 kilometer stretch far quicker than a horse and rider could. Messages could be sent over 200 kilometers in just two minutes, thus creating an efficient communication method for troops to communicate. These flags were mostly used by the navy, as they could be strung high onto the ship's sails. Ships could communicate to passing ships, and also to shore. THE TELEGRAPH was the most commonly used mode of communication during battle. They would be used to inform families of their soldiers passing, capture, or wounding. Soldiers often sent telegrams to their families about their travels or that they had survived a battle. Governments and war correspondents could communicate effectively and efficiently. The messages were often kept abbreviated due to the expense of sending one. The word telegraph is derived from Greek and means “to write far.” Messages were sent between stations by transmitting electrical signals through wires that would have been laid by troops. Transmissions would be sent in morse code, then translated to English on the other end. The electric telegraph transformed wartime communication as bases could communicate almost instantly, immensely improving reaction time to attacks. Unfortunately, the telegraph was quickly phased out for more modern equipment. Technology was heavy, expensive, and required delicate care to remain working. Wires would be subject to gunfire and bombs, causing them to constantly require repairs. It wasn’t uncommon for a signaller to have to fix 40 cables per day. Wireless transmissions became a priority during the Second World War. FLARES were used by the army, navy, and air force during the Great War to both signal and illuminate the field. Flares of various colours would have been used for signalling, while white flares would be for flashes of light. Oftentimes, they would tie flares to trip wires to catch sight of approaching troops. Many soldiers reported issues with the flares as the paper cartridges would fall apart when damp. Flare guns were often called Very Lights by British forces. A song from the trenches was called ‘When Very Lights are Shining’ and was sung to the tune of ‘When Irish Eyes are Smiling’. The song ends with the line ‘Sure when Very Lights are shining, ‘Tis rum or lead for you.’ To find out more about wartime communication, visit the 8th Hussars Museum, 66 Broad Street, Unit 3, Sussex, New Brunswick.

8 Comments

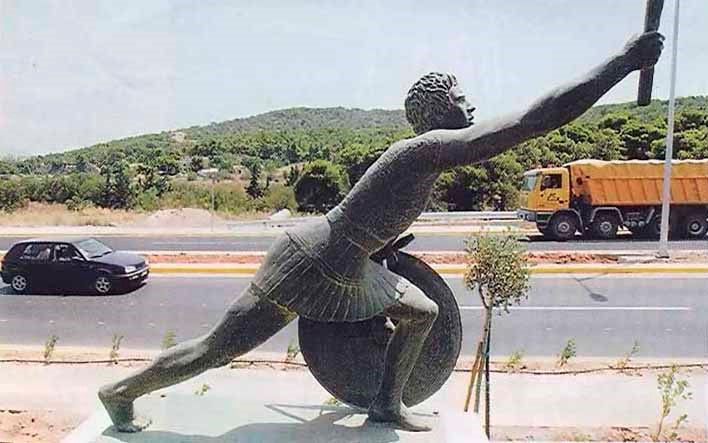

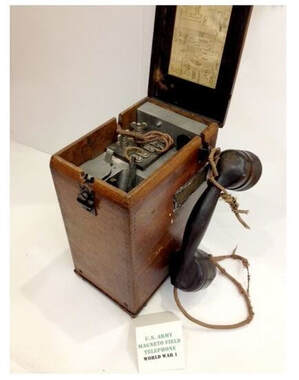

Runners: The origin of the runner began with a traditional story from Ancient Greece. During the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC there was a messenger soldier named Pheidippides who ran 26.2 miles to Athens to deliver important news of a Greek victory over the Persians. After the soldier made his announcement, he collapsed and died from exhaustion. Now, the modern day 25-mile race is called the Marathon, it is to commemorate the soldier and his extensive efforts for his city. During several major wars in our history there were many ways to communicate. In the early days there were specific soldiers nicknamed “Runners”. These soldiers’ primary roles were to deliver critical information on foot from one command to the other. While serving, the runners had to have extensive knowledge of the terrain they were travelling on. If you were a runner during a war you had to master certain skills such as: Map-reading, speed, and precision. It was easy to tell which soldier was a runner as they wore a red armband on their left forearm. During the Great War specifically there were more options of communication available. However, most countries preferred having runners. Radio communication was a relatively new thing in the early years of the 20th century, so it was very unreliable and technical difficulties happened frequently. When the new breakthrough of field telephones appeared it too caused many problems. The field telephone was very difficult and time consuming to set up. During the heat and chaos of battle, there was very little time; and messages had to be delivered as soon as possible. As such the runners were more effective compared to the commonly used carrier pigeons. However, these birds provided great use during the war, but sometimes they missed their targets. Because of this, critical information couldn’t be delivered when needed. When being a runner your job would bring you to defy death almost every single time you were put to a destination. Runners were mainly targeted by enemy soldiers to make sure that messages did not reach their intended destination. While being heavily targeted by enemy troops the runners had a lot of ground to cover. The average distance between the trenches and on the front line was about 150 yards. If a runner was spotted by enemy troops, they had to avoid heavy machine gun fire, artillery, and snipers to deliver their messages safely.  Riders: Motorcycle and Horseback: While Runners were very important to the war effort there were other means of communication that also did their part to help the Canadians succeed in battle. An alternative method of communicating were Riders. These were soldiers that were mounted on Horseback or Motorcycle. Horseback riders were more common in early wars because of their flexible availability. Riders rode across deadly terrain to deliver important messages to their officers. Similarly with Runners the Riders had to memorize deadly terrain and navigate swiftly to complete their missions. Commonly enough Riders were often targeted by enemy soldiers, and the Rider had to think quickly to make sure him and his horse would survive while being targeted and to deliver the critical information on time.  Moving onto a different type of Rider, these specific soldiers rode on motorcycles. When in tough times during the war and there were no more horses to help riders deliver messages, they used motorcycles to transport information from one camp to another. However, motorcycles were used more in the Second World War. As such they were still in their early stages and technical difficulties occurred constantly. The Riders had a difficult time being sneaky when using these vehicles, the element of surprise was lost, and enemy soldiers could easily spot them out because of all the noise the motorcycle created. Field telephones were widely used during the First World War. These devices used wire lines, occasionally commandeering civilian circuits when they were available. This new advancement in technology replaced previous methods of communication such as: flag signals and the telegraph. The telephone made communication almost instantaneous. There was no longer a need to worry about loss of life when delivering messages. However, there were new threats that effected all countries using these devices. The average telephone line only spanned 7 miles. So, each telephone could only be within that limit of each other to communicate. This prevented the soldiers from going far distances to deliver messages. When this occurred, it was easy for enemies to intercept and destroy lines of communication. For one day the average soldier repaired approximately 40 lines of telephone wire. Not only were lines destroyed by enemies they were also destroyed by the chaos of warfare. The field telephone was an exceptional advancement for military technology. However, there were some faults, it made communication a lot more efficient. Nevertheless, it was time consuming to set up and repair, but it proved its way into being one of the most efficient forms of communication in modern war.

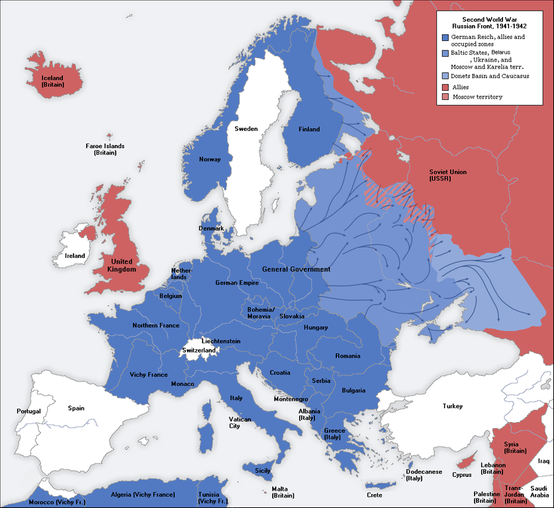

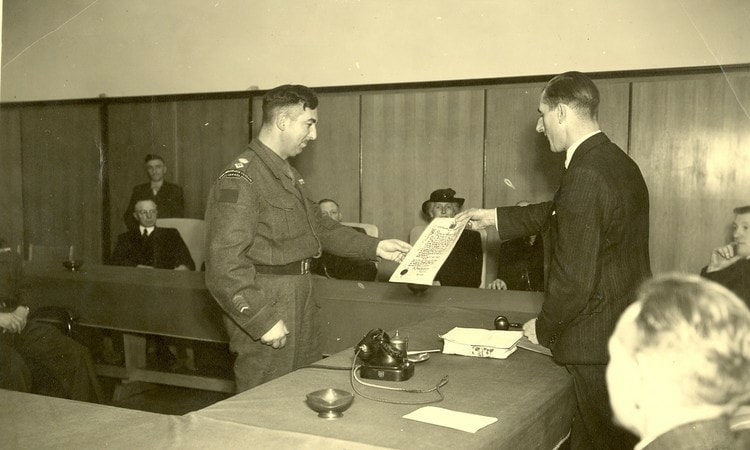

To conclude, communication was a very important asset in any war. From running across the Mediterranean to sending men on horseback on the Italian front. Delivering messages is a key component to strategy and it must occur with great diligence and skill. One question I will leave here. What do you think is the most efficient form of communication? Read the 2 parts of this blog and send us a comment! In March of 1945, the war was rapidly drawing to a close. The German Siegfried Line had broken, and Allied troops were beginning the final leg of their liberation of Europe. The 8th Hussars, however, were given a different target. West of the Rhine lay the Netherlands, occupied still by German forces after years of war. The people were starving, weary of the brutality of their overlords. The 8th Hussars, along with other elements of the 1st Canadian Corps, were sent into the Kingdom of the Netherlands to cast off the German yoke. Their first task was to defend members of the 11th Brigade, who were clearing the line between Nijmegen and Arnhem. It was fairly quiet work, consisting mainly of patrolling the area to check on potential enemy positions. When they determined what locations the Wehrmacht used, they shelled them. A few skirmishes resulted from contact with enemy patrols, but there was little opposition in that region. As these patrols occurred, the rest of the regiment was preparing to move up. On the 12th of April, the Hussars were moving to the Ijsselmeer. The Canadians were tasked with seizing two bridgeheads in Arnhem and Apeldoorn. The Hussars themselves were actually sent into Germany, on their way to the Dutch town of Wehl. By the 14th, the British had taken Arnhem, and the Hussars entered the city. Amid its ruins, ravaged by the Germans during their departure, the Hussars received their orders. They, along with their sister regiments, were to clean out the 30-mile area between Arnhem and the Ijsselmeer in four days. It was, quite appropriately, named Operation Cleanser. The next day, the 8th Hussars were confounded by roadblocks as they drove to the Ijsselmeer. As they broke through them, they were fired upon by the enemy. The attack moved to the Arnhem airport, which provided no cover to the Hussars. In one of the most dramatic and daring movements the regiment ever performed, the 8th Hussars crossed the Arnhem airfield, surrounding every infantry-filled scout car with tanks, so that the German machine guns couldn't get a shot at them. The field was crossed, but not without casualties. Their progress through the Dutch countryside was by no means easy. Their lines were rugged and tanks were lost to the elements or the enemy. Still, the blitzkrieg of Operation Cleanser pressed on, and, by the second day, were near to the city of Barneveld, just seven miles from the Ijsselmeer. There, the Hussars witnessed firsthand the tragedy of the German occupation. Hundreds of Dutch civilians were starving, while the traitorous Dutch S.S. were harassing the Hussars from the shelter of a nearby wood. A whole regiment of artillery focused their fire on the forest where the enemy took cover, and incinerated all but seven of the 300 contained therein. The following day, the Canadians advanced to the town of Voorthuizen, from where they would move to take Putten and cut off the Germans in Holland from those in the eastern Netherlands. It was a turbulent day, but the 1st Division triumphed, with the town falling into Allied hands by evening. At the day's end, the 8th Hussars found themselves a mile from Putten and the sea. Behind them lay a trail of chaos extending back to Arnhem. Emboldened by their successes, the Colonel of the regiment ordered a night attack on Putten, the town where Operation Cleanser was to end. Putten was not to fall that night, however, as A Squadron rode into the town, they were ambushed by German troops and driven back. Their will unbroken, they regrouped, and, at 9 o' clock the next morning, the 8th Hussars took the town. After five years of Nazi oppression, the people of Putten rejoiced, taking to the streets and throwing their arms around their liberators. Not long after taking Putten and closing the Allied line to the Ijsselmeer, the 8th Hussars were sent off again with the 5th Division to partake in one last great battle. In the northernmost part of Holland there lay the port of Delfzijl, a German stronghold boasting impressive fortifications and a garrison of 3000 men. By April 24th, the Regiment found themselves supporting four battalions of infantry surrounding the city, a struggle that lasted for eight days. Attack after attack moved through the sodden spring fields of Holland, waves of infantry followed by the great steel tanks of the Hussars. Each time the Germans would advance in counter-attack, and each time they were dispatched at point-blank range by the Canadians. Many tanks were lost in the muck, but still the advance continued, capturing guns and men, and seizing metre after metre of occupied territory. As the victorious hand of the Allied armies closed slowly around Nazi Germany, so too did the 5th Division, 8th Hussars included, close around the port of Delfzijl. Eventually, after eight days of blood and mud, the garrison of Delfzijl surrendered, marching out of the city in hundreds, and into the waiting arms of the 5th Division. The war ended days later, and the people of the Netherlands rejoiced in their newfound freedom. In the village of Eelde, the Regiment was presented with a parchment and gold medal from the mayor and council of the municipality commending them for their role in liberating the town. The people of Eelde still honour the 8th Hussars to this day by raising our town flag on May 5th, the anniversary of the day they were liberated. Thousands of miles across the sea, Sussex raises theirs.

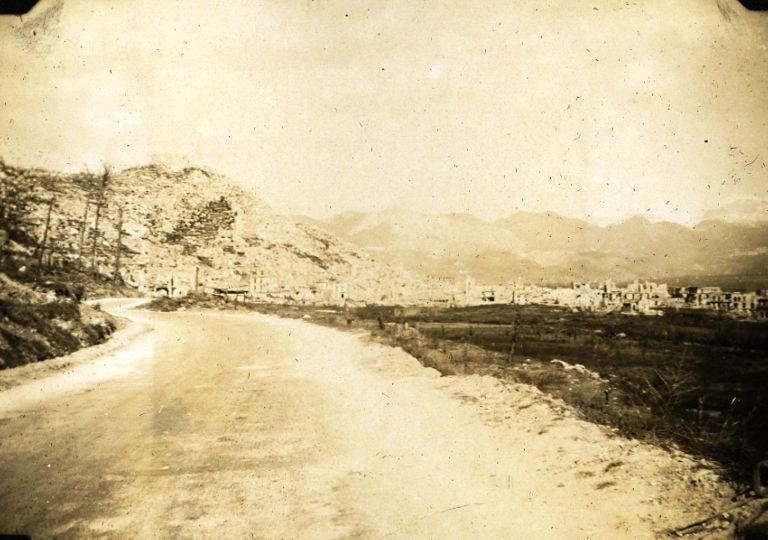

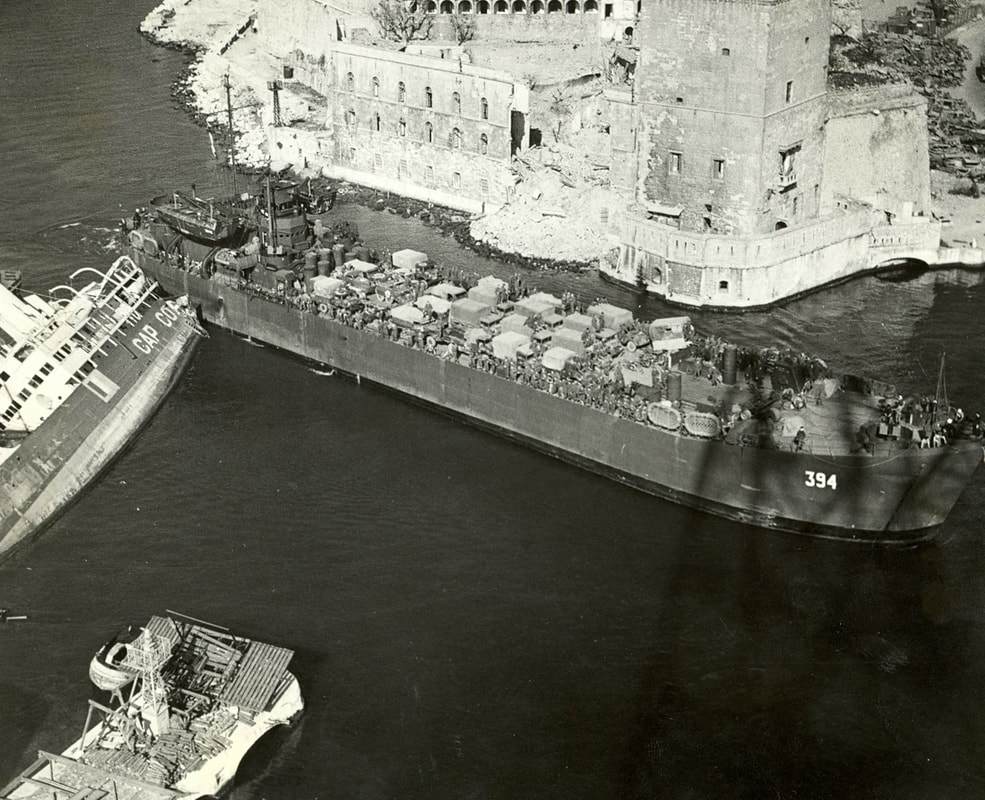

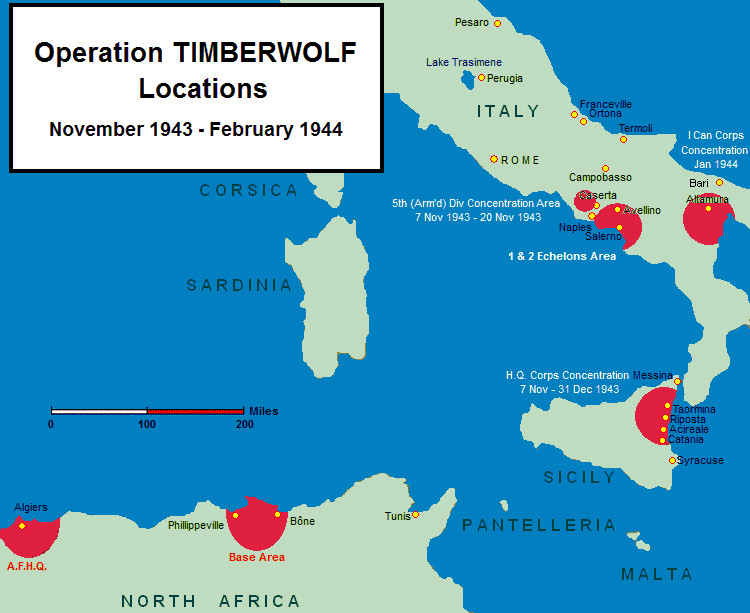

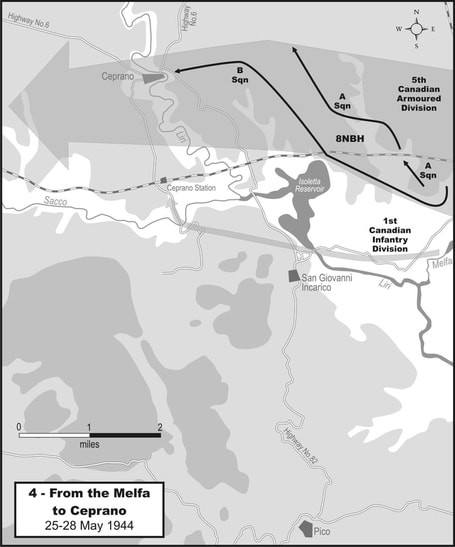

Operation Diadem was the codename used to denote the Battle of the Liri Valley. This battle took place from 11 May to 4 June 1944 in western Italy. If Allied Forces could break through in the Liri Valley, it would be a straight shot onto Rome. However, the campaign would not be easy. Using the mountainous terrain, the Germans had created a series of defensive lines that cut across the Italian landscape. Allied Forces would have to knock the Germans from their defensive perches in order to march on Rome. A night assault was launched against the first hurdle in the Liri Valley, the Gustav Line. Allied Forces breached the line and eventually broke it, forcing the Germans to retreat to the Hitler Line on 17/18 May. Following this, preparation began for the assault on the Hitler Line. The 5th Armoured Regiment (8th Princess Louise’s New Brunswick Hussars) would be moved to the front to take part in the Liri Valley campaign from 18 to 30 May. The Regiment began moving on the 18th, it would take several days for the Hussars to reach their destination. Traffic congestion kept the roads clogged; the Regiment would finally reach their preliminary staging ground on the 20th. Orders came down the next day, Allied Forces were to assault the Hitler Line on the 23rd. On the 22nd, the Hussars were given their regimental orders. Operation Chesterfield would see the Hussars and their attached infantry regiments form a beachhead across the Melfa River, after Allied Forces had cleaved the Hitler Line. From there, the Regiment was to exploit towards Ceprano.

However, in order to get to the Melfa, and Ceprano beyond, a hole had to be punched in the Hitler Line. This line served as the defensive fallback for the Germans retreating from the Gustav Line. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and 5th Canadian Armoured Division, as part of the British 8th Army, drove a wedge into this line on 24 May. After extensive fighting, this wedge was widened into a breach. The Hussars were hurled into this breach. In the breach, the men found chaos. The Germans were retreating before the advance of the Canadians. However, their retreat was sporadic. The Hussars encountered clusters of infantry and anti-tanks guns. Some of the Germans ran, others surrendered, and those that did neither were engaged and eliminated. After a series of these encounters, the Hussars had made their way to an assembly point just before the Melfa. They would spend the night there, after silencing some German artillery. On the morning of the 25th, the regiment began their crossing to provide support to the infantry on the other side. To get there, the regiment had to take their tanks up a donkey path that had been widened by the engineers. At the top, the tanks of C Squadron encountered some stiff resistance, but after several minutes of heavy fighting, this immediate resistance was cleared. However, the regiment would experience consistent mortar strikes throughout the night of the 25th. With the Hitler Line penetrated, the Germans began their fighting retreat. In the process they provided no fixed front, and so the battle became fluid. The enemy was engaged where he could be found: in houses, clusters of trees, and the villages. For the Hussars, the town of Ceprano was the next target. This small town on the Liri River was a key strategic target as it was at a crossroads heading out of the Valley. Taking this town would hamper the German effort to withdraw their forces from the Hitler Line. When the infantry finally entered Ceprano, all they found was a deserted town, the Germans had already withdrawn. Unfortunately, the Hussars were stuck on the other side of the Liri River as there was no bridge to get across. So, the Hussars waited; it would be the 28th before the engineers were brought forward to put up a bridge. However, once on the other side, the advance slowed considerably. The dense foliage prevented the easy movement of tanks and material to continue the advance. Eventually, the terrain made the Sherman tanks ineffectual. Command gave the word on the 30th, the Hussars were to halt the advance their part in the Battle of the Liri Valley Their role was finished. With the Hitler Line smashed, Allied Forces weaved their way through the Liri Valley and unto the Italian prize, Rome. The laurels would go to the Americans who, under the command of General Clark, entered a Rome empty of Germans on 4 June 1944, ending the Battle of the Liri Valley. Following the capture of Montecchio, the Allies were poised to consolidate their gains and pierce further through the Gothic Line. The Cape Breton Highlanders led the way, capturing Monte Marrone on the night of 31 August, 1944. With the path clear, the 8th New Brunswick Hussars could move their tanks up the hill and dig in. From their imposing position, they were just over a kilometer away from the twin peaks of Monte Luro and Point 253. Situated on a spur on Point 253 lay the town of Tomba de Pesaro, the next objective awaiting the Canadians. A barrage of 75mm shell fire from Hussar M4 Sherman tanks signalled the start of the battle. The Axis defenders furiously returned fire, immediately knocking out Lieutenant Bill Spencer’s tank. Lorne Fraser and Harper were subsequently killed. Other tanks fared better, with enemy armour-piercing shells bouncing off their turrets. Around 12:00 noon, under heavy anti-tank and mortar fire, Major Howard Keirstead ordered No. 2 troop to move about a kilometer and a half to the left of the main force and mount a flanking maneuver. Once No. 2 troop arrived, they surveyed Tomba de Pesaro through binoculars, identifying targets and potential enemy positions. Marked targets were then blasted with 75mm shells and machine-gun fire. Enemy anti-tank crews reacted quickly and returned fire, although they were swiftly knocked out after giving away their position. Nevertheless, several enemy high-explosive shells hit their mark, and damaged the gun on one of the Hussar tanks. The firing continued and ammo began to run low. One of the tanks risked moving up the crest of the hill and opened up on several houses with machine-gun fire. White flags were waved and surrendering Italian troops emerged from the houses. However, the fighting was far from over and stubborn enemy resistance remained firmly entrenched in the town. By the afternoon, Point 253 had fallen to the combined attack of the Irish Regiment and C Squadron from the 8th Hussars. The stage was set to move into the town of Tomba de Pesaro. While staging for the main attack, the tanks came upon several hidden concentrations of German infantry. They proved no match for the heavy Canadian armour, and some seventy soon surrendered. The tanks began moving up the ridge towards the town, with infantry from the Irish Regiment riding atop the tanks. Advancing uphill along rocky terrain was difficult, and several tanks lost their tracks. Around 1800 hours, the main attack on the town began, with the tanks providing heavy covering fire as they advanced. The Germans never fired back however. Sensing an opportunity, the infantry dismounted and entered the town. Rather than encountering resistance, they found the Germans had abandoned the town and fell back. In celebration, the infantry hung a banner that read, “Bobby Clark-ville – In Bounds to All Canadian Troops”, in honour of the Commanding Officer of the Irish Regiment. Lieutenant-Colonel Clark himself had nothing but accolades for Cliff McEwen and the 8th Hussars. As a token of appreciation, he handed McEwan a gallon of rum. Thanks to the combined efforts of the 8th New Brunswick Hussars and the Irish Regiment of Canada, Tomba de Pesaro was now firmly in the hands of Allied forces. The Gothic Line had been definitively breached, and the Germans were once again forced to fall back. Slowly but surely, the Italian campaign was reaching its conclusion.

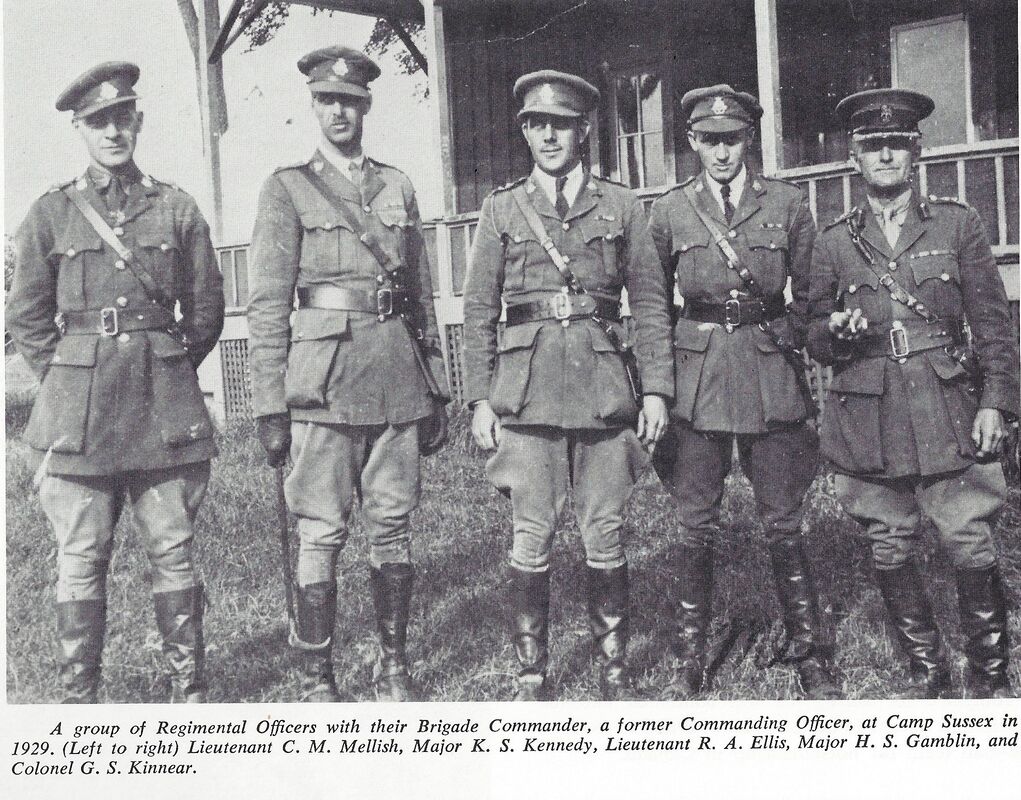

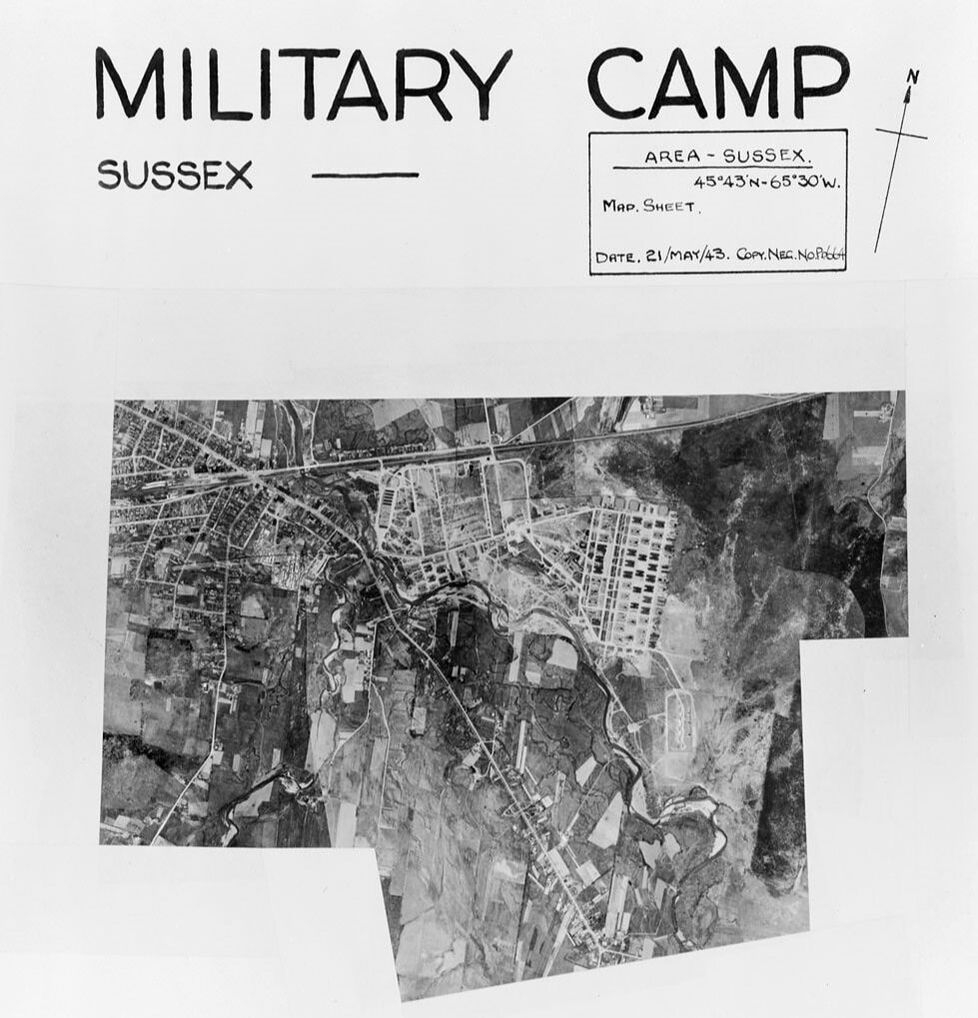

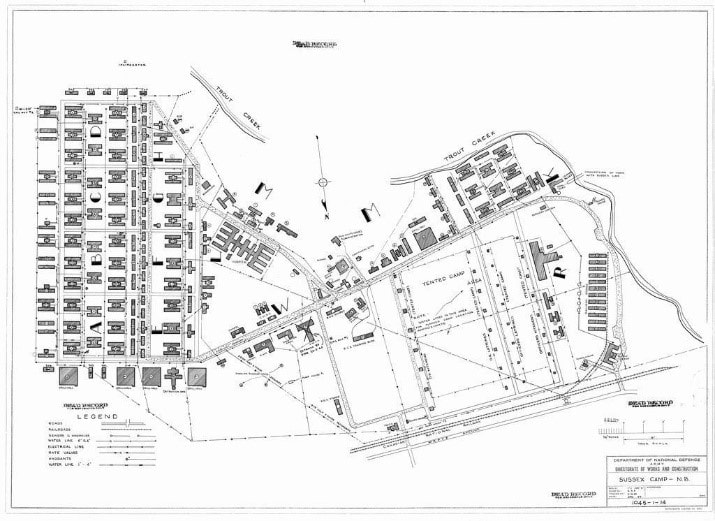

To find out more, visit the 8th Hussars Museum, 66 Broad Street, Unit 3, Sussex, New Brunswick.  The Battle of Liri Valley was an Allied Operation that, if successful, would give the Allies a direct corridor unto Rome. In order to gain access to the main highway to Rome, the Melfa River had to be forded. The Canadians from the Westminster Regiment and Lord Strathcona’s Horse would be the first units across. The Westminster’s would cross in the early morning hours of the 24th of May 1944. They established, and held, a beachhead against stiff German resistance until they were reinforced. The 5th Armoured Regiment (8th Princess Louise New Brunswick Hussars) would be ordered forward to the Melfa Crossing to help enlarge the beachhead on the other side. At 0800 hours on the 24th, the Regiment began their move. However, due to traffic, the regiment would not be at their muster-point until 1100 hours. German artillery fire began raining down on the tanks as they moved, but the shellfire could not penetrate the Shermans. From there, the regiment would be on the move again at 1500 hours. It would be during this move that the Hussars would see their first action of the Melfa Crossing. The Germans had begun pulling back, and command wanted them stopped. So, the regiment swung to cut across the German withdrawal and the Reconnaissance tanks were sent out to sweep the area. Unexpectedly, German infantry began firing at these lead tanks. A Squadron was sent in to assist in clearing this resistance. During this brief engagement, two Sherman tanks became stuck after attempting to make their way through a gulley. In the same Gulley, the Hussars found a German Panther. From where they were stuck, none of the tanks could fire on the other. Some small-arms fire was exchanged and a German killed. The rest surrendered. Ultimately, the action on the 24th would be short lived and sporadic. The German withdrawal meant that there were no defined enemy positions, instead the regiment engaged pockets of infantry and the occasional Panther as they stumbled upon them. As the day closed on the 24th, the regiment was redirected back to the Melfa Crossing. Enemy tanks had been sighted by the Canadian infantry, and the Hussars were needed to stave off a possible attack. As darkness fell, the regiment settled down to get what sleep they could, all the while the shellfire rained down on them.  The regiment would be resupplied on the morning of the 25th. From there, the Hussars moved to their new muster-point. At 1500 hours, the regiment would begin crossing the Melfa River. A donkey trail had been widened by the engineers to allow the tanks passage to the top of the bank on the other side. It was a nerve-wracking climb. At one point, a terrified young driver abandoned an anti-tank gun he was towing to the beachhead. The driver had completely blocked the trail and had stalled the regiment’s advance. Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson ran from his tank and cajoled him into continuing the advance. On the other side of the river, the regiment linked up with the Cape Bretons and took over the advance. The beachhead had to be expanded. In setting out to accomplish that task, the Hussars would drive into the teeth of a German ambush. Shortly after 1700 hours, a withering German fire would be hurled at the Hussars. The anti-tank fire came at them with unparalleled ferocity. The volume of fire was such that the gunners were practically blind. There was no where to go but forward, so the Hussars charged blindly ahead their guns firing at random. In desperation, the gunners keep firing, wherever it was suspected that a German gun might lie, a shell was fired off. Three tanks had been destroyed by the Germans, some going up in flames. Another, that belonging to Major Lane, was targeted for destruction. The Germans managed to knock it out of commission, in the process seriously wounding the Major and his crew. The Hussars kept pressing on, as one tank was knocked out, another would come to fill its place. In this manner, the regiment made it nearer to the German positions. With the threat posed by the closing Shermans, the Germans began their withdrawal. By this time, the other squadrons of the regiment had made it up from the Melfa Crossing. The Hussars had eliminated several 75mm guns and a self-propelled anti-tank gun. This brief conflict lasted only a quarter of an hour. With the Germans driven back in the immediate area, the day’s action for the Hussars would end. The Hussars tried to get what sleep they could amidst the German shelling, for tomorrow the fight would go on. Despite earning its reputation as a nascent military power on the battlefields of Europe, the Canadian armed forces fell into precipitous decline following the end of the First World War. After the November 11th Armistice and the subsequent signing of the Treaty of Versailles, much of the then large and battle-hardened Canadian Army was demobilized. By 1920, Camp Sussex, which had trained units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force headed overseas, was a shadow of its former glory. Appalled by the state of affairs, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Markham made the decision to whip the most important fixtures of the Camp back into shape. The government eventually provided some funds, but most of the repairs came out of the Regiment’s coffers. The repairs were a success, and by 1921, the Regiment was back to holding summer militia training camps, albeit on a much smaller scale than before. However, cutbacks had taken their toll. The first summer, 21 officers, 88 men, and 78 horses mustered for training. The number of men who showed up for training dwindled the following year, and by 1923, each horse was shared by two men. Meanwhile, federal money had dried up, and the Hussars frequently turned men away because they could not afford them. Consequently, training focused on building up a nucleus of key men to form the backbone of the Regiment in the event of war. By the late 1920s, there was growing realization that the era of sword and saddle was coming to a close. Mechanization, as it was understood, was the wave of the future. Many cavalrymen, however, were skeptical of these trends and continued to do whatever they could to maintain the relevancy of cavalry. The 1930s proved even more challenging for the 8th Hussars, and the Canadian Militia as a whole. The Great Depression, the most calamitous economic downturn known to industrial society, began in 1929. Amid growing unemployment and shrinking government revenue, the Hussars came under growing financial strain. In 1931, the Regiment was informed it would be allocated a mere $675 for training, the lowest amount ever. Later, the financial situation deteriorated further, and Ottawa informed the Regiment there would be no funds for summer training and only a small amount for evening drill. As a result, much of the training had to be conducted on a voluntary basis, out of the pockets of the Regiment’s officers. Nevertheless, the men made the best of it. A.T. Ganong took personal responsibility for the success of the Regiment, and his leadership was instrumental in its survival through this period. His successor, Lieutenant-Colonel Keltie Kennedy became the inheritor of this legacy and became, in the words of the historian Douglas How, “one of the stoutest champions the Regiment has ever had.” Colonel Kennedy’s leadership inspired the men to go above and beyond, and his steady hand was instrumental in keeping up morale during this difficult period When Kennedy was still a Major, he suggested to a high-ranking officer at dinner that the 8th Hussars machine-gun troop would like to attend the central marching-gun camp at Valcartier, Quebec. The senior officer scoffed at the idea, highlighting the unfairness of sending mere militiamen into competition with specialist machine-gun units. Major Kennedy responded by saying that if the troop performed poorly, he would pay for its trip out of pocket. The Hampton troop went to Valcartier in the summer of 1935 and bested every other unit there. In many respects, the performance of the 8th Hussars machine-gun troop reflected the essence of the era. Short on cash and manpower, the Hussars did what the could with what they had, in many cases with astounding results. With another world war around the corner, this training proved invaluable as Canada once again rebuilt its army To find out more about the 8th Hussars and the interwar period, visit the 8th Hussars Museum, 66 Broad Street, Unit 3, Sussex, New Brunswick.

The Canadians had been in Italy for a year when they liberated Ravenna. It was December 4th, 1944. The Fifth Division is still celebrated today for its bravery in freeing the ancient city. As their actions in Ravenna succeeded, however, another failed. The First Division participated in a hastily-organised attack across the Lamone River, which was repelled by the Germans and forced a Canadian retreat. Together, the Royal Canadian Regiment and the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment suffered close to 200 casualties, some of which were inflicted by their own artillery as they clung to the riverbank. Despite this setback, command began the organization of a second offensive across the Lamone, a week from the failure of the first. Nothing was spared in preparing for this attack. Both Canadian divisions, the 1st and 5th, were to attack simultaneously, while a British brigade would conduct a feint attack nearby. The Desert Air Force would support the ground attack by bombing enemy positions on the other side of the river. The attack went of the night of December 10th, 1944. Several infantry divisions used boats and inflatable bridges to cross the river, swelled 60 feet across by Italy’s winter rains. The 48th Cape Breton Highlanders, Carleton and Yorks and West Nova Scotians all crossed that night. Engineers erected bridgeheads across the river. The enemy had been disorganized by the tanks of the 12th Royal Tank Regiment of Britain, and hadn’t recovered when the initial assault began. The advance was swift and effective. By two in the morning, the Canadians had captured several towns on the north bank of the Lamone, and taken over a hundred prisoners. The Desert Air Force was doing its job well, performing 312 sorties on December 11th alone. It was on the eleventh that the Germans regrouped and counterattacked in two places, hoping to regain some of their lost ground. The attacks were held off by the Westminster Motor Regiment, who would later distinguish themselves beside the 8th Hussars during the liberation of the Netherlands. The Allies held their ground, while the engineers completed the bridgeheads. By the twelfth, the rest of the Allied troops were ready to cross. All this time, the 8th Hussars had been making their way north from Cervia to Ravenna, their mood sour. Their long-time commander, Lt.-Col. G. W. Robinson, had been promoted out of the regiment and sent to Holland to command the 2nd Armoured Brigade. In addition to the loss of a dear leader, the 8th Hussars were to act as infantry when they arrived in Ravenna. Major Bob Ross, the acting commander of the regiment, had haggled with the brass and persuaded them to allow C Squadron to keep their tanks. The other two squadrons, however, were left high and dry, and were drilled as infantry on arriving in Ravenna. There they remained, from the ninth of December to the 12th, when they were told to attack the town of Mezzano, eight miles north of Ravenna on the Lamone. They crossed the river early on the 12th, the new infantry of A and B Squadrons clinging to the tanks of C. Their point of crossing was a Villanova, from where they moved northeast up the Via Aguta. The 8th Hussars would attack Mezzano from the north. Ultimately, however, Mezzano proved empty. There were no Germans for them to fight in the town itself. Actual contact with the enemy was brief, and occurred just east of town. Major Ross moved the regiment along, taking occasional fire from snipers and machine guns. 8th Hussar patrols pushed 2000 yards to the Naviglio canal, allowing for the engineers to their rear to finish constructing a bridge over the Lamone that would allow the rest of the army to cross. Only one man was wounded: during a skirmish, Sergeant Patterson of Recce Troop was shot by a sniper. Altogether, the 8th Hussars killed about 80 enemy soldiers that day. It was later that night, at about 11 o’ clock, that the Germans retaliated. To the left of the Regiment’s position, the 12th Brigade of infantry had begun an attack across the Naviglio canal. Shells soared across the plain, crashing into the fertile Lombard ground around where the 8th Hussars were halted. Machine gun fire shattered the stillness of the Italian night. In response, the Regiment dug in, just as any infantry regiment would have, and defended themselves. The Navoglio offensive would eventually succeed, but not without cost. The Princess Louise Dragoons lost 21 men to death and another 46 to capture. The Lanark and Renfrews were holed up in a house across the Naviglio for two days, losing 38 men in the process. The Hussars position remained on the near side of the Naviglio until the 15th.

Eventually, their new colonel arrived, relieving Major Ross of his temporary command. On the 15th, the Regiment was told they could stop playing infantry and have their tanks back. It was a joyous occasion for every 8th Hussar on the field. After the Lamone experiment in infantry, Princess Louise’s Regiment was home, insofar as they were armoured again. The 16th was spent with their vehicles, checking them over and preparing them to ride into the bloody, unknown future of the Italian Campaign. During the autumn of 1944, the 8th Hussars took part in a great Allied offensive intended to break the Gothic Line; a 200-mile long, 10-mile deep wall of German artillery and fortifications. Stretching from the port of La Spezia on the Tyrrhenian Sea to the city of Pesaro on Italy’s eastern shore, the Gothic Line provided a near-impenetrable barrier to the heartland of the Italian Social Republic, the Nazi puppet state that played host to all the German troops in Italy. If the Allies were to liberate Italy, the Gothic Line had to fall. After a long summer spent training and relaxing in the Roman countryside, the 8th Hussars mounted their tanks for another campaign. They travelled north, battling their way through the Apennine Mountains, skirting German defenses as they went. As August faded and the first traces of autumn were felt, the Canadians came to the narrow plain that separated the mountains from the Adriatic Sea. Between them and their destination of Rimini lay 40 kilometers of alternating valleys and ridges, bristling with the strength of the German 10th Army. The 8th Hussars, as part of the 5th Division, were a part of the initial force tasked with breaching the Gothic Line and pushing to Rimini, a contrast to their role in the battle of Monte Cassino, where they had played a supporting part in the action. The first action they saw on the Gothic Line was the battle at Montecchio, in which the Cape Breton Highlanders attacked three times before withdrawing. Eventually, the Hussars came to their assistance, and they captured the village, taking 130 prisoners. At the same time, A Squadron defended Point 111 a short distance away. The villages of Monte Luro, Monte Marrone, and Tomba di Pesaro fell shortly afterwards to the advancing Canadians. On September 3rd, 1944, the Canadian forces arrived at Misano, a small village perched atop a ridge, and one of many anchors of the Gothic Line. The Royal Canadian Regiment and the Westminster Regiment led the charge, with the 8th Hussars providing armoured support to the infantry units. There was no major battle at Misano Ridge. Instead, the next four days would prove to be a series of confused skirmishes between the attacking Canadians and the Germans, now on the defensive. A Lieutenant Burns of the RCR would bravely lead a bayonet charge against the enemy, driving them from the town square. The 48th Highlanders advanced to attack, but were forced to retreat when heavy enemy fire pinned them down. The 8th Hussars attacked the hamlet of Besanigo, a hamlet on the seaward slope of Misano Ridge, early on the 4th of September. Mortars held them up, with "B" Squadron pinned on the ridge for most of the day, as "A" Squadron tried futilely to help. They fired smoke shells at enemy guns on neighbouring Coriano Ridge, but the enemy were not fazed, and the Hussars did not capture Besanigo. The 8th Hussars lost six tanks that day, but one Hussar received the Regiment's first Distinguished Conduct Medal during the battle. Sgt. W. P. Fleck dismounted his tank when daylight was running out and making it hard for crew commanders to see anything. Fleck led his tanks to their objective, killing five Germans with a machine-carbine and capturing eight more. He was wounded by shrapnel, but continued on with his injury until he passed out from loss of blood. The following morning, the Cape Breton Highlanders and the Irish Regiment of Canada were able to capture Besagino. Two days previous, the Hastings and Prince Edward companies captured the village of Santa Maria di Scacciano from the enemy. By the end of the fifth, all of Misano Ridge was under Canadian control. The battle for the Gothic Line, however, was just getting started. A ridge over, at Coriano, the Germans began a vicious mortar and shelling campaign, a resistance unanticipated by the Allies, but calculated and executed coldly and precisely by the defending Nazis. Just as the first skirmishes were beginning to pay off, the advance to Rimini was abruptly halted.

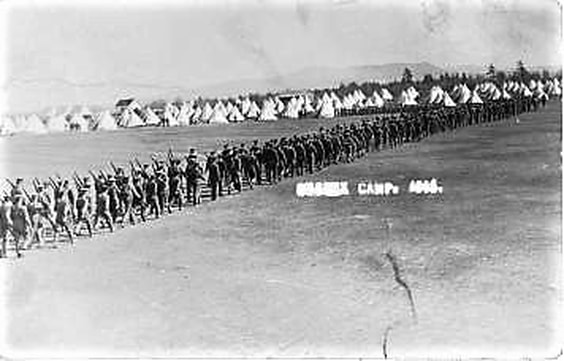

For the next ten days, the Canadians fought for every scrap of land they could hold. The center of that struggle, a simple, idyllic hilltop village, was to be the sight of one of the most destructive and hard-fought battles in the 8th Hussars' entire career as a regiment. In the end, Misano was a warm-up, paling in comparison to the utter, indiscriminate destruction of Coriano Ridge. The decades following the end of the First World War would see Camp Sussex decline as an epicentre of military training in the province. Several of the local militias, like the 8th Hussars and New Brunswick Rangers, would still assemble at the Camp for annual training. Beyond this, the Camp would be relegated to secondary importance, especially as the Great Depression began ravaging the country. With the government tightening the strings on the treasury, funding for the militia would become scarce. Austerity would become the only policy available to many militia’s and their training centres. However, prior to the onset of the depression, many militia regiments managed to make good use of the Camp. The 8th Hussars Officer’s Bungalow, constructed in 1904 and renovated following the First World War, would become a focal point of community activity in Sussex.  Situated in Camp Sussex, this building would welcome visitors from the Town of Sussex and officers from other militias, in the process becoming famous for its hospitality. Besides this, a new militia, the 7th Machine Gun Battalion was formed, and did much of their training, in Camp Sussex following the First World War. As one last hurrah before the onset of depression, Canada-wide Merit Cup Competition, an annual cavalry competition, was held in Camp Sussex in 1930. But, with the onset of the Great Depression, funding for the militia would be curtailed. Pay cuts, fewer days training, and for many voluntary training became the norm during the depression years. However, as the country began moving out of the depression, Camp Sussex would go on to retake its place as the pre-eminent military training centre in Atlantic Canada. As the situation in Europe began to deteriorate in the late 1930s, the militia began to prepare. For the Hussars, this meant new methods of training. The First World War had shown that the use of cavalry in modern war was untenable. So, the Hussars began to mechanize. With some confiscated Model T-4s, the regiment would practice maneuvers in the fields of Camp Sussex.  The outbreak of the Second World War would be the catalyst that would reinvigorate the Camp. In the early years of the war, a massive building programme was undertaken. There were not enough beds to house all the soldiers that were being sent to the Camp for training. From 1940-1941, the Camp was expanded to house approximately 10 000 men at a time. To accomplish this, H-hut barracks were constructed on the grounds, covering a significant portion of the Camp. Canteens, officers’ quarters, administrative buildings, latrines, hospital, all the infrastructure that the Camp needed was smashed onto the grounds. Yet, so great was the influx of men, the bell tents still had to be used to quarter some of the men. During the early years of the war, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, and elements of the 7th Canadian Infantry Division would be trained in Camp Sussex. Each division comprised approximately 10 000 men. The 3rd and 4th were overseas combat divisions, the 7th was a home division. Training included learning to operate heavy weapons like the 2 inch and 3 inch mortars at the McGregor Brook Range, rifle and machine gun practice, amphibious assaults, map reading, administrative tasks, and many other skills essential for combat.  As the war progressed, the A34 Special Officer’s Training Centre was established at Camp Sussex. It was under the command of Brigadier Milton Gregg, a recipient of the Victoria Cross in the First World War. The British Army had experienced a high rate of casualties among their junior officers. As such, the A34 training centre would train the CANLOAN officers; these officers volunteered to be loaned to the British Army. Approximately 650 officers would be sent to Camp Sussex to be trained under Brigadier Gregg before being shipped to British Regiments. The close of the Second World War would ring the death-knell for Camp Sussex. As the Canadian Army was repatriated home, the operation of the Camp came under government scrutiny. Size was a problem; the Camp simply did not have enough room to accommodate both the soldiers and the land needed for training. So, an old idea was revived, Gagetown New Brunswick would be selected as the new Canadian Forces Base for New Brunswick. In the meantime, Camp Sussex would still be used. The 8th Hussars had 6 Sherman tanks located at the Camp, they trained with these until they were removed by the government in the late 1950s. . For a while, the Black Watch was headquartered in the Camp following the end of the War. When CFB Gagetown opened in 1958, military training began to be concentrated there. For Camp Sussex, this saw much of its infrastructure taken away. Some of the H-huts were towed across Trout Creek and converted into residential complexes. One training hall became the York Arena in Fredericton, another became the Kings County Stadium. The Gas Hut were taken to Peter Street and made into a home. The tank hanger now houses the Agricultural Museum. Finally, the land itself was sold to the Town of Sussex in the early 1970s. The Gregg Armouries on Leonard Drive, which houses B Squadron of the 8th Canadian Hussars, is the only military connection to what was the premier training base in Atlantic Canada. And so, after 100 years of military service, thus ended Camp Sussex. The Battle of Montecchio 30-31 August 1944 By Matthew GambleBy early summer, 1944, Axis forces in Italy were on the backfoot. Allied breakthroughs at Anzio and Cassino meant that German forces were at risk of being surrounded and cut-off. However, disagreements between British and American commanders over who would be first to liberate Rome gave German forces time to retreat to the Gothic Line and consolidate their defences. As a result, a new line of dangerous fortifications needed to be breached by the allies. The 8th New Brunswick Hussars were to play a role in this operation. On the 29th of August, 1944, the Regiment moved into position in the hills south of the picturesque town of Foglia. Their objective: cross the valley below and occupy the high ground before occupying the town of Montecchio. The Germans had other plans, and elements of the German 10th Army were hastily digging-in in preparation for the inevitable Canadian offensive. A formidable 14-foot anti-tank ditch was dug, and machine-guns and anti-tank guns were positioned on the high ground with interlocking fields of fire. Montecchio lay surrounded by these formidable defences. It would not be an easy fight. In the battle to come, B Squadron, with infantry support provided by the Cape Breton Highlanders, was to take Point 120, a prominent knoll to the west of the town. Meanwhile, A Squadron, with infantry support provided by the Perth Regiment, was to take Point 111, the edge of a long ridge in the area. Finally, C Squadron, supported by the Irish Regiment of Canada, was to take the high ground surrounding Tomba di Pesaro. The attack began at 1730 hours on the night of the 30th, and was met by feeble German resistance. The Canadians had caught the Germans off-guard as they hurriedly tried to man their positions. Seizing the opportunity, Major Howard Keirstead and his tank advanced down the valley to join the Cape Bretons. This time, the Germans were prepared, and the Major’s tank faced a wall of enemy fire. Captain Bob McLeod and his tanks were eager to join the battle, but were held up in a traffic jam by a Provost. McLeod continued by motorcycle under fire in a bid to find Keirstead, who ordered the tanks moved up. With the tanks still being held up by the Provost, McLeod made a call to Colonel Somerville, seeking permission to get his tanks moving again. The Cape Bretons encountered fierce German resistance at Point 120. Despite tank support from the Hussars, the enemy was not to be dislodged. Nevertheless, A Squadron, under the command of Frenchy Blanchet, found more success at Point 111. Artillery fire proved very effective at neutralizing German gun emplacements, and the hill was taken without heavy casualties. The next day brought the inevitable German counterattack. The line held, and the Regiment consolidated its gains, with Cliff McEwen and C Squadron reinforcing Point 111. From the high ground, they pounded enemy positions in and around Montecchio. The fire was effective, and the Irish Regiment easily mopped up remaining German resistance. Outflanked, the Germans defending Point 120 quickly fell soon after. Lacking infantry support, A Squadron encountered much heavier resistance as they attempted to take the high ground at Point 136. Ten Hussar tanks were knocked out by enemy fire, and the attack was blunted. Major Blanchet and his tanks were forced to fall back into a defensive position until infantry support arrived. After linking up with the Perths, the Hussars were finally able to take Point 136 from its exhausted defenders.

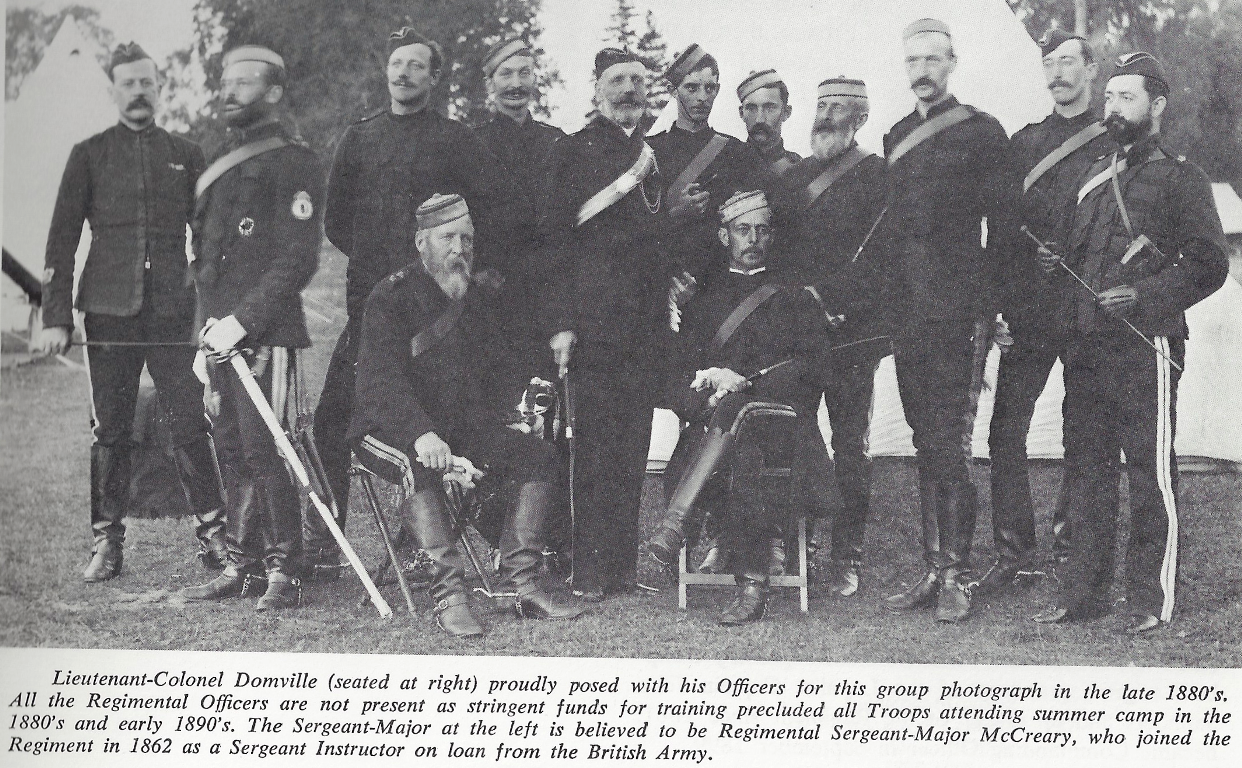

From their newly-conquered commanding positions above the valley, the Hussars took stock of the cost of their conquest. Burnt out tanks littered the valley, and the Regiment spent the next several hours digging graves. The grim cost of war. Fighting in and around Montecchio was just a taste of what was to come in later battles, as the Allies breached the formidable defences of the Gothic Line. To find out more about this story, and the 8th Hussars in the Italian campaign, visit the 8th Hussars Museum on 66 Broad Street, in the historic Sussex Train Station.  Camp Sussex was the largest Military Base in Atlantic Canada. It was officially opened in 1893. However, the land had been used for training by local militias as early as the 1870s. For example, the 8th Princess Louise's New Brunswick Regiment of Cavalry trained on the grounds in 1885; there were so many men in attendance that the band was brought in for the duration of the Regiment’s time in Camp. In addition to this, the regiment would parade at the future camp in 1889. As the decades passed, Camp Sussex would become the premier military training installation of the Maritimes until it was eclipsed, and eventually shut down in the 1970s, by the opening of CFB Gagetown. The area chosen by the Dominion Government in 1893 for the Militia Camp was located near the heart of the Town of Sussex. The Camp Ground’s terrain consisted of field, forest, and stream. The terrain would be suitable for cavalry, infantry, and artillery. The most prominent cavalry regiment at Camp Sussex were the 8th Hussars. The 74th Battalion trained at the camp every year until the regiment was disbanded following the Second World War. The Newcastle and Woodstock artillery regiments frequented Camp Sussex numerous times. However, training in these early decades would be performed mostly in the summer and fall months as the camp had no permanent buildings. For the cavalry, this allowed them to perform drills in the dry summer months, which helped prevent injury to horse and rider. For the men attending camp, they would make use of the Bell tent, with 10 men assigned per tent. Eventually, these tents would be mounted on a wooden base to keep the men and their equipment off the damp ground. The first permanent structure that came to Camp Sussex was the Armoury. It was built in 1904 by the Dominion Government. The Armoury would be assigned to the 74th Battalion and the 8th Hussars to use for storage and supplies. This building would remain in service until after the Second World War. In the years leading up to the First World War, militia training would reach its zenith at Camp Sussex. This is despite the fact that a soldier’s pay was often negligible. For example, a soldier in the 74th Battalion could receive anywhere from 0.50 to 0.85 cents per day in 1907. The 8th Hussars used a comparable pay structure. However, the Hussars could receive an extra $1.50 as the Government would rent their horses. Notwithstanding the low wages, many militia regiments would train in Camp Sussex leading up to the First World War. Annual militia training was a key component of Dominion defense; as such, the militia regiments were mobilized annually to take part in 1 to 2 weeks of training in the summer. This annual training did not preclude the regiment’s from conducting their own training camps throughout the year. In Military District No. 7, New Brunswick, this annual training often saw over 1000 men gathered in Camp Sussex to perform drills, practice their shooting, and go on parade. As a result, the annual militia training became a local attraction for the citizens of the Town of Sussex and the surrounding countryside. A lively social life was struck up centering around the officers and men in Camp Sussex. The Cavalry charges and ceremonies often brought out the men and ladies of the town to watch. For example, the Camp held a parade, which many people flocked to attend, on 22 June 1911 to celebrate the Coronation of King George V. These were the idyllic years of Camp Sussex; however, they were not to last, the Camp was about to undergo a metamorphosis in the explosive years of the First World War. The First World War would highlight the importance of Camp Sussex. For example, a Serbian Mobilization Battalion was established at the camp to train Serbs for combat. Besides this, 1000s of men would be shipped by train through the Sussex train station and into the Camp. Some of these regiments were: the 55th Battalion, 104th Overseas Battalion, 26th (New Brunswick) Battalion, 74th Battalion (New Brunswick Rangers), 64th Battalion (The Princess Louise Fusiliers). These regiments all made Camp Sussex their home before they embarked for the United Kingdom, and the battlefields of Europe. The training done by these men was done primarily in a Camp with few permanent buildings. While there were some dining halls for the officers and administrative buildings, the men would spend most of their time in the Bell tents used since the Camp opened.

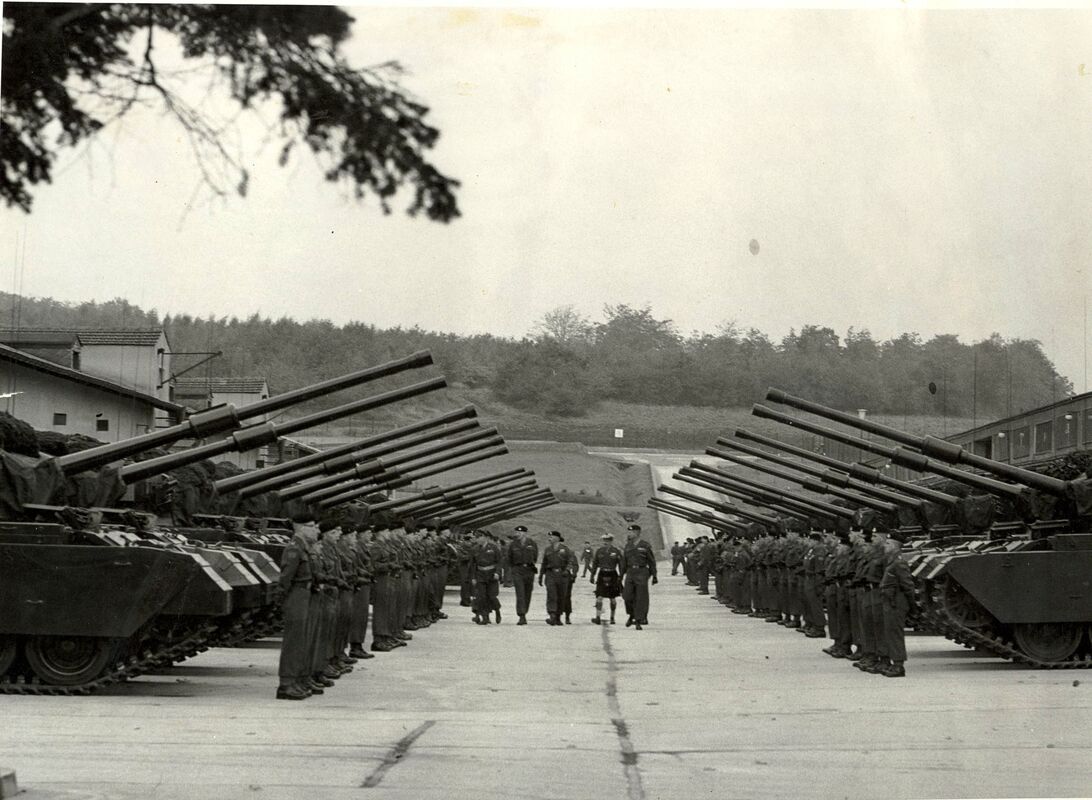

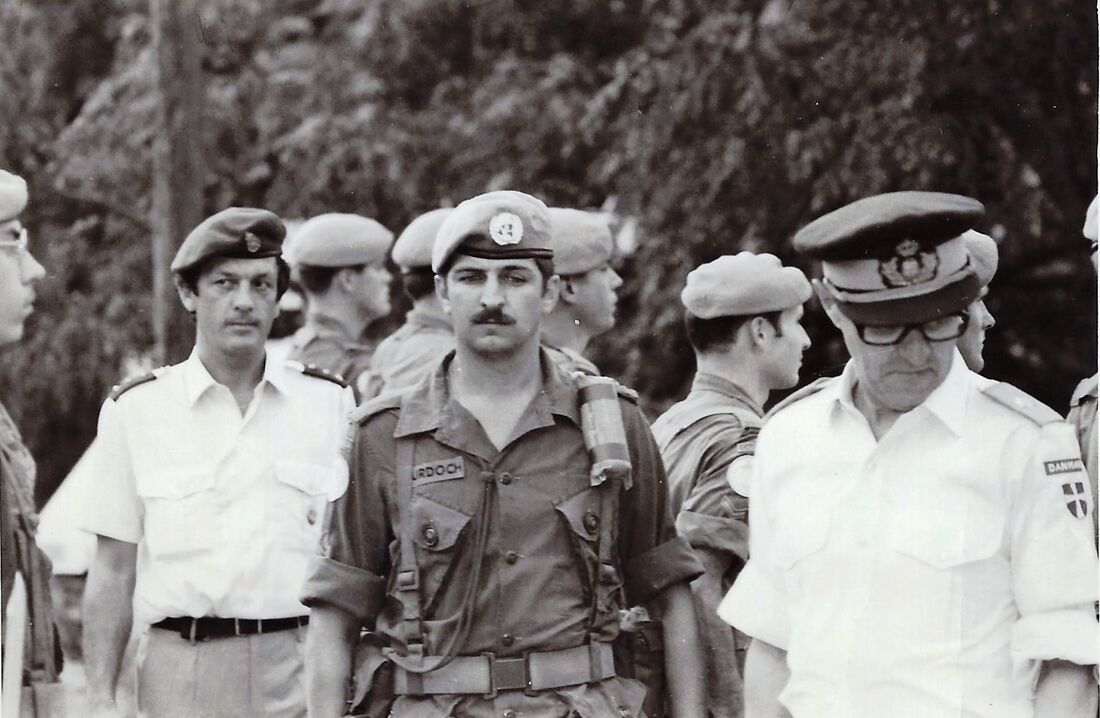

As the First World War approached its final year, the Canadian Government placed an emphasis on recruiting more soldiers. In response, the 1st Mobilization Depot Battalion was raised and headquartered at Camp Sussex in April of 1918. Their task was to increase the number of recruits training to replace those men lost at the front. Overseeing the Battalion was Lieutenant-Colonel James McAvity. However, the establishment of the Depot Battalion would be the last great development at Camp Sussex for the next two decades. 75 years ago, the guns of the Second World War fell silent. The Hussars already knew in late April, early May of 45 that the war was all but done, just tell the Germans that. From the War Diary of 03 -05 May, 1945, this is what is written. 3 May 45. Thunder showers predominate throughout the day. The regiment chiefly spent the day reorganizing personnel and generally getting sorted out after the recent operation. The tank crews enjoyed a much longed for shower and change of clothing. Capt R.H. Dunn and Lt J.J.M. Scovil left for England for a period of duty as instructors. Major G.R.H. Ross was ordered to proceed to GODLINZE (3831) and take command of a force to be designated the “ROSS” Force. It was composed of the following: “C” Squadron 8NBH who were moved from HEVESKES (4824) and a Dutch Independent Company. The task was to patrol the area and to act as an anti invasion force as the enemy were still in strength on the FRISIAN ISLANDS. By dusk the force was complete and situated as ordered. Attached as appendix is the order denoting the boundaries and and sectors of the “ROSS” force. Holland 1/100,000 4 May 45. The weather was very changeable with heavy showers GRONINGEN W Sheet M1 throughout the day. 2 Officers and 30 Other Ranks left at 0300 hrs MR 218067 on privilege leave to the UK along with 4 Other Ranks on EMDEN L1 rotational leave to Canada. Lt- Col J. W. Eaton held an “O” GRONINGEN Sheet M1 E Group at 1330 hrs, attended by all squadron and echelon commanders at which he stated that the present role of the division was an occupational force with the task of holding and patrolling the coast line from the Ems River to Ijssel River, our regimental task until the 6 May 45 being to patrol the sector of coast from 383398 to 40296 occupied by the “ROSS” Force. Lt–Col J. W. Eaton stated that all captured staff cars in the regiment must be registered and controlled by an officer of field rank. “V” Day celebrations will be supervised as much as possible to avoid accidents. Due to a number of tanks being bogged down and left separate from the squadrons in the last actions, considerable difficulty arose over delivery of rations to these crews. A meeting of the 2 ICs of squadrons is to be held by the Quartermaster to discuss the problems of rations. The squadron commanders were asked for further nominations of awards resulting from the last actions. “A” and “B” Squadrons spent the day doing maintenance, painting and general refitting of tanks. Capt J.W. Stobbart, Auxiliary Services, has arranged to show a film twice a week for all ranks. At 2230 hrs the long awaited for message was received from Rear 5 Cdn Armd Bde, “Cancel all offensive operations, cease fire at 0800 hrs 5 May 45”. The “ROSS” Force was situated as follows: one troop “C” Squadron and one platoon Dutch Independent Company at SPIJK (4033) and one troop “C” Squadron and one platoon Dutch Independent Company at ZIJLDIJK (3434). The remainder and force HQ were stationed at GODLINZE (3831). The enthusiastic Dutch were allowed to do all patrols under supervision of the “C” Squadron troop leaders concerned. The patrol reports were nil. A dance was held by the officer’s mess during the evening. 05 May 45. The day dawned amidst scattered showers with a cold, strong breeze blowing. The day was chiefly spent by the maintaining of vehicles and by personnel having their clothing cleaned etc., and the resumption of the out of action schedule. The “ROSS” Force spent a quiet day. All reports of any unusual activity being received. During the afternoon the “ROSS” Force was relieved by the BCDs and “C” Squadron returned to their former quarters at PATERSWOLDE (2106). A regimental officers mess is now functioning. As a result of the two operations many new faces were amongst the Officers and men. After everything was said and done, the Regiment would spend another eight months in Europe before returning home to Sussex in late January 1946. Sgt. Don Abbott 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise’s) Historical Archives NCO Canadian Forces Europe and the 8th Canadian Hussars By Matthew GambleFollowing the calamity of the Second World War, Europe stood divided. The Western Allies occupied much of Western Europe, while Eastern Europe fell into the Soviet orbit. Soon, tensions between the two camps became irreconcilable, and a tense standoff developed. The United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and others, responded with the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Collective security was institutionalized under Article Five of the Treaty; thus, an attack on one member would be considered an attack on all. This principle came to form the cornerstone of security architecture in Europe. As part of its NATO commitments, Ottawa established Canadian Forces Europe, a military formation to be stationed in West Germany, the frontline of the Cold War. It was not until December 1958 that the Regiment was informed it would join the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group in Germany the following year. Preparations began in the new year and continued throughout the spring and summer. Major Brennan's advance party left for Germany in late September 1959, while Lieutenant-Colonel Radley-Walters and the main force departed from Quebec City several weeks later. By mid-November, the Hussars were stationed at Fort Beausejour, just west of Iserlohn in West-Central Germany. The Fort was described as "a neat and cozy complex of barrack blocks, hangars, messes, and canteen, with a postage stamp-size training area in back." While in Germany, the Regiment was to keep in top shape, as there was a very real danger that the Cold War could turn hot at a moments notice. Soldiers conducted intense training, and polished their skills in tank gunnery, camouflage, small arms, and crew training. The Centurion tanks were pushed to their limits, with a few almost being lost in a bog on one occasion. Meanwhile, various military exercises were conducted with NATO allies, and such excursions often brought the Hussars into the streets of German towns and villages. Additional time was filled with sports and competitions including boxing, volleyball, and softball. The Regiment returned to Canada in 1962, but three years later, 'C' Squadron would return to Germany to provide reconnaissance for 4 Canadian Infantry Brigade Group until 1970. In 1987, the 8th Canadian Hussars were once again deployed to Germany, this time to CFB Lahr, relieving the Royal Canadian Dragoons. Although the Cold War was winding down, the Regiment remained on alert. By this time, the organizational sophistication of NATO had increased substantially, as did the scope and scale of military exercises. The Regiment took part in several large maneuvers, the most notable of which being the annual Reforger exercises, which simulated rapid deployment of military forces to Germany in event of a major conflict with the Soviet Union and/or its allies. Yet, the Regiment's time in Germany was also filled with sports of all kinds. Particular emphasis was placed on team building and competitive sports, and various trophies and awards were often up for grabs. At the same time, a high premium was placed on positive engagement with local communities, and the Regimental armouries were occasionally opened up to the public. All of these moments have been well-documented by Regimental photographers, and the photos are on file at the museum archive, both in print and digitally. When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the Regiment had at its disposal 77 Leopard C1 tanks, 20 Lynx armoured reconnaissance vehicles, 36 M113 armoured personnel carriers, 2 M577 command vehicles, and 6 Bergepanzer armoured recovery vehicles. Indeed, in the event of a major conflict, the 8th Canadian Hussars would have formed the armoured backbone of Canadian forces in Germany. By 1993, a major drawdown of forces was taking place across the continent, and Canadian Forces Europe was disbanded. The Hussars subsequently returned to Canada with another overseas deployment under their belts. CFB Lahr subsequently closed its doors for the last time in 1994.

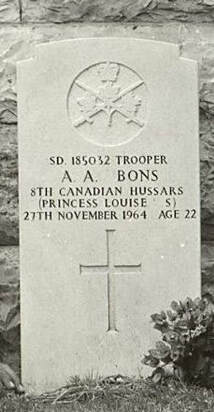

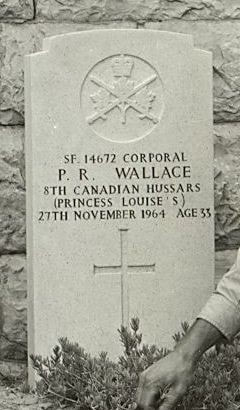

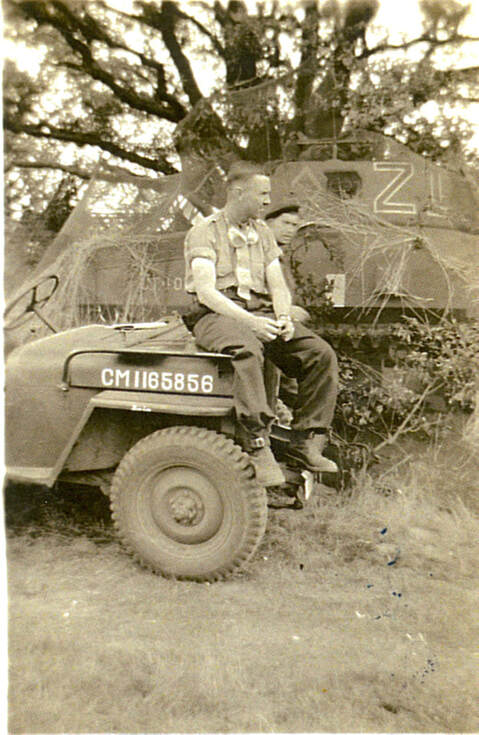

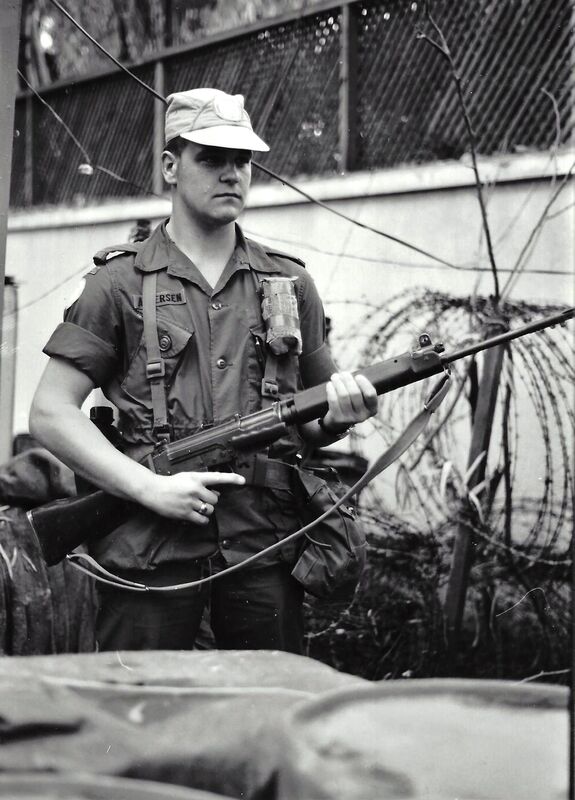

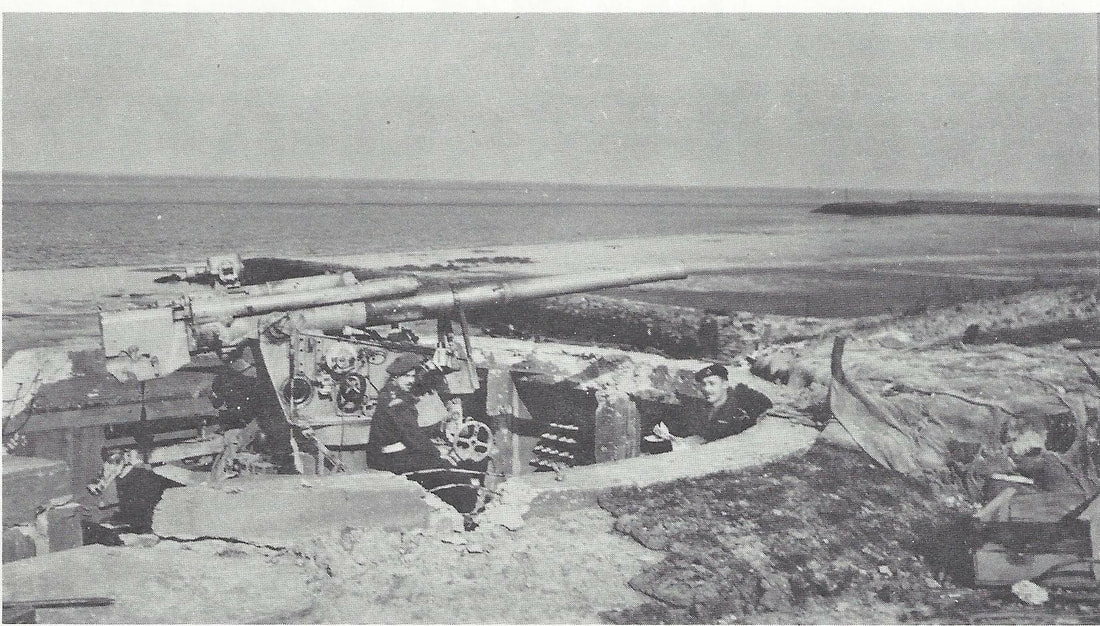

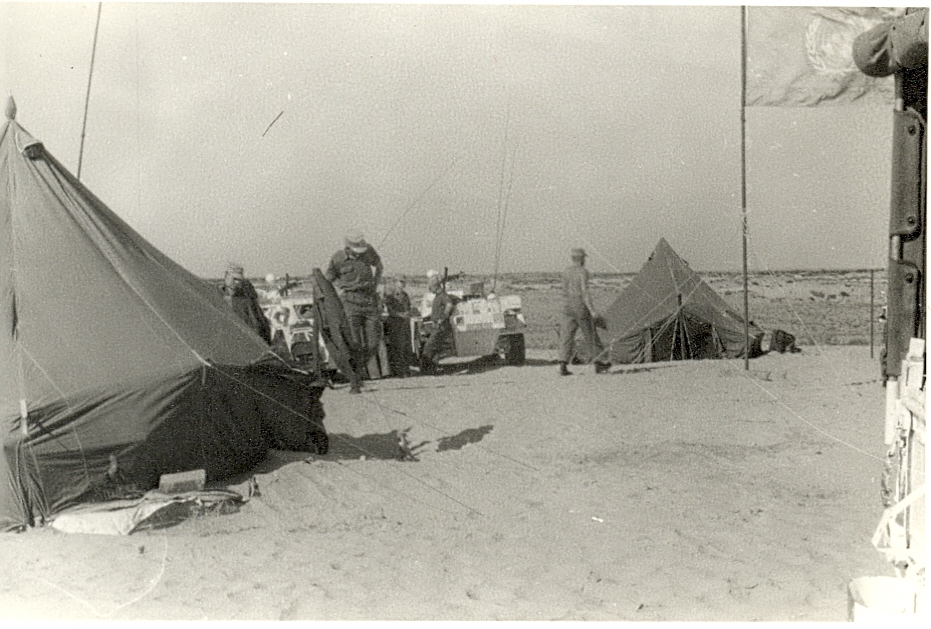

United Nations Emergency Force I: The 8th Canadian Hussars in Egypt 1964-1966 By: Hayden Johnston2/25/2020 Following the Suez Crisis, the United Nations’ Emergency Force I would remain in Egypt until 1967. This mission was critical to the prevention of war between the Israelis and Egyptians. As a result of the longevity of this mission, the 8th Canadian Hussars would be tasked with returning to man a sector of the armistice line on the Gaza Strip. The Hussars would deploy ‘D’ and ‘A’ Squadrons for 12-month rotations in the country starting in 1964. As Peacekeepers, the Hussars were to provide a stabilizing presence in the region. Unfortunately, their deployment was not without risk, two Hussars would be killed while serving with the Peacekeeping Force in Gaza. Camp Rafah - Egypt In February of 1964, D Squadron made landfall at Camp Rafah, Egypt, in the Gaza Strip. Here, the Canadians would serve as a shield between the Israel Defense Force and the Egyptian military. These men were to take over the duties of Lord Strathcona’s Horse, who would be repatriated to Canada. The Regiment’s main operational centre within Camp Rafah was Fort Worthington. When not in the Camp, D Squadron maintained two permanent outposts along their assigned section of the ‘International Frontier.’ The northernmost position was Fort Robinson; thereafter, the line was held by the Brazilians. The Southernmost position was called Fort Saunders; further south, the line would be held by the Yugoslavs. Between these two posts, the Squadron would be responsible for patrolling over 30 miles of border. In terms of logistics, the Squadron was divided into troops. This ensured that they had sufficient manpower to maintain a continual presence along their defensive line. Moreover, it allowed for the rotation of soldiers into, and out of, the demarcation zone. Finally, this arrangement allowed the frontline soldiers to be taken from the line for rest and relaxation. The Hussars would be equipped with American Jeeps, sidearm's, and several Browning machine guns for good measure. Fully equipped, the Hussars would be subsumed in their peacekeeping duties. The border area falling under the operational control of the United Nations was beset by several challenges. First, the Hussars had to be vigilant of the operations being conducted by the Israelis and Arabs on both sides of the border. However, a more pertinent issue was the constant violations of the border by the Bedouins, nomads, and Palestinians. This could often raise the ire of Israeli soldiers resulting in skirmishing. While this proved challenging, it was not the most pressing danger experienced by the Hussars. They had to contend with thousands of mines, which remained buried following the disengagement of the Israelis and Egyptians. Tragedy would soon take two lives. While out making their rounds, two Hussars would pick up a Bedouin infiltrator. These three men would make the return journey to Camp Rafah. On the way, their Jeep would trigger an anti-tank mine, killing the three men and destroying their Jeep. Corporal Paul Wallace and Trooper Adrian Bons would be buried with full military honours at the Gaza War Cemetery. D Squadron would finish their peacekeeping tour without further incident. A Squadron would relieve D Squadron in February of 1965. These Hussars set out to improve the relationship with the indigenous peoples. This included providing provisions for the Bedouins and engaging with local leaders. The most serious event of the Squadron's deployment occurred when one of the Squadron's personnel threatened other Hussars with his sub-machine gun. Fortunately, this threat was quickly neutralized. Ultimately, a lively social life sprang-up for the Hussars. There were dances and inter-squadron sports to keep the peacekeepers occupied. A Squadron would be the last of the Hussars to participate in Peacekeeping with the UNEFI in Gaza. At the end of 1965, the Squadron was informed that they would be rotated out. A Squadron would lower their flags in February of 1966. Their positions would be taken up by the Brazilians in the North and the Yugoslavs in the South. While no additional Hussars would go on to serve in Egypt, this would not be the last Peacekeeping mission for the 8th Canadian Hussars. Hussars Observation Post - Sinai Desert Bibliography Information Technology Section/ Department of Public Information. United Nations Emergency Force I https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/past/unefi.htm Sabretache, 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise's). Issue 1/66. CFB Petawawa, 30 June 1966 Sabretache, 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise's). 1964 The 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise's) 1962-1987 Editors note: As a memorial to Tpr Bons and Cpl Wallace, their vehicle pennant, recovered from the site, is on permanent display at the 8th Hussars Museum in Sussex, NB

United Nations Emergency Force I: The 8th Canadian Hussars in Egypt 1958-1959 By: Hayden Johnston2/6/2020  The Suez Crisis, 1956, was an international controversy involving Great Britain, France, Egypt, and Israel. President Nasser of Egypt sought Western Investment to help his government construct a hydroelectric dam. He was rebuffed by the International Community. As a result, his government nationalized the Suez Canal. This Canal was run by a consortium of French and British companies. Angered by the nationalization, and the explicit threat to their trade, the French and British conspired with the Israelis to retake the canal. The Israel Defense Force invaded Egypt. French and British paratroopers were sent to the canal to ‘protect’ it during the ensuing turbulence. In an effort to pre-empt the actions of the Superpowers, Lester Pearson’s Peacekeeping initiative would be implemented. It would be in 1956 that an international contingent of soldiers would embark for Egypt. While they came from different countries, they would serve under the flag of the United Nations. They came to stand as a shield between the fighting Egyptians and Israelis. Canadians were among those sent, and the 8th Canadian Hussars were among the Canadians. Camp Rafah, Egypt A Reconnaissance Squadron of the Hussars would make landfall in Egypt in 1958. They set out from Canada and arrived in Camp Rafah early in February. While there, the REECE Squadron would be responsible for 35 miles of the ‘International Frontier.’ As such, they would be equipped with Ferret Scout Cars and a number of supplementary vehicles. As Peacekeepers, the Hussars would be lightly armed, their main armaments being sidearms and rifles. To assist with logistics, Operational Posts would be constructed at the furthest extremes of the International Frontier. Winnipeg would be in the North and Toronto would be located in the South. Initially, these outposts were sparse; However, as the mission progressed, the Hussars were able to co-opt some base engineers to help improve the amenities at the outposts. Using the material at hand, these outposts would be equipped with look-out towers. From these posts, the Hussars maintained regular patrols of the Sinai Desert. Air Observation, Egypt  The Hussars ability to patrol the desert was greatly enhanced when the United Nations implemented aerial reconnaissance of the region. Three times per week, a Hussar would be sent with an RCAF pilot to observe the desert. This policy would enable the Squadron to more effectively police their border. This was important considering the fact that the Bedouins, desert nomads, frequently disregarded the border to make repeated trips into the desert. Peacekeeping was not without its tribulations. For example, several Hussars would come under enemy fire while out patrolling. As they were too far from the shooters to return counter-fire, the Hussars made a quick getaway by crossing to the Israeli side of the border. Once there, they were able to take temporary shelter with some Israelis, before being escorted back to the Egyptian side of the border. Outside of this incident, a more common danger to the Hussars were the presence of leftover mines from previous conflicts. For the Hussars, most of these mines were of no concern. The only exception being the deliberate planting of a mine on the Squadron’s patrol route. Fortunately, no Hussars were killed, although several were wounded. One of the final incidences in Egypt occurred when the Squadron captured Israelis who had conducted a raid against Bedouins in Egypt. The Israelis would be promptly released back to Israel, where they were punished for their actions.  Hussars Outpost, Sinai Desert Ultimately, the Hussars would be repatriated back to Canada in 1959. Their mission to Gaza had been a success. The Hussars left behind a border that was more secure than when they had arrived. Additionally, their efforts at improving the infrastructure on the International Frontier would be key to the success of future deployments to that area. In a few short years, their comrades in ‘A’ and ‘D’ Squadron would return to the same region to pick up where the Reconnaissance Squadron had left off.

Guiding the 8th Hussars through some of its bloodiest fighting in the Second World War, the "trusty and well-beloved George William Robinson Esquire" forged a reputation as one of the Regiment's greatest and most well-respected commanding officers. Robinson assumed command of the 8th Princess Louise's New Brunswick Hussars in 1942, after joining the Regiment as a Major. Robinson proved himself early on, and he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel (LCol) by June. Upon taking command, Robinson sought to transform the Hussars into a competent fighting force, capable of facing battle hardened Axis troops. Initially, some of the Hussars, mostly Maritimers, were apprehensive about having a native Ontarian as their Commanding Officer. This soon changed, however, as the men quickly came to realize their new leader was not only a highly effective commander, but one who cared deeply for their safety and well-being. Under Robinson's command, the Hussars embarked on an extensive training program. The new C.O. understood well the gravity of the situation facing the men, and thus ensured no stone was left unturned. Nevertheless, Robinson was a fair man, and ensured everyone under his command received downtime when deserved. As time progressed, the men forged close bonds. They would soon be put to the test.