By 1920, Camp Sussex, which had trained units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force headed overseas, was a shadow of its former glory. Appalled by the state of affairs, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Markham made the decision to whip the most important fixtures of the Camp back into shape. The government eventually provided some funds, but most of the repairs came out of the Regiment’s coffers. The repairs were a success, and by 1921, the Regiment was back to holding summer militia training camps, albeit on a much smaller scale than before.

By the late 1920s, there was growing realization that the era of sword and saddle was coming to a close. Mechanization, as it was understood, was the wave of the future. Many cavalrymen, however, were skeptical of these trends and continued to do whatever they could to maintain the relevancy of cavalry.

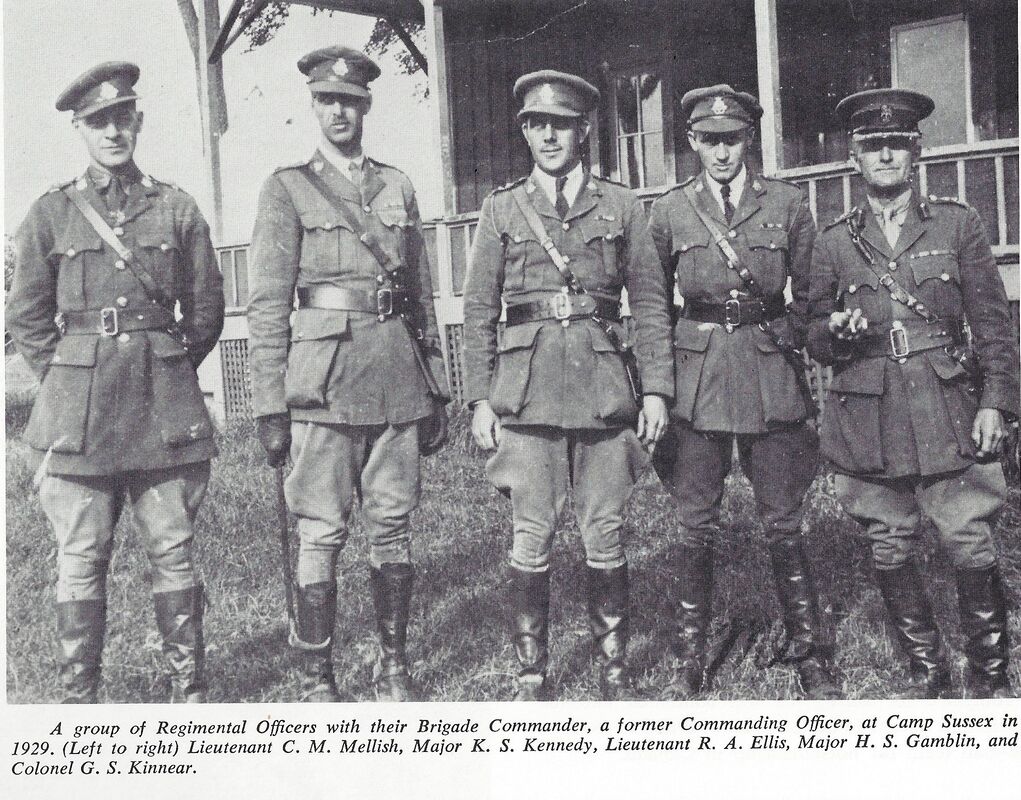

Nevertheless, the men made the best of it. A.T. Ganong took personal responsibility for the success of the Regiment, and his leadership was instrumental in its survival through this period. His successor, Lieutenant-Colonel Keltie Kennedy became the inheritor of this legacy and became, in the words of the historian Douglas How, “one of the stoutest champions the Regiment has ever had.” Colonel Kennedy’s leadership inspired the men to go above and beyond, and his steady hand was instrumental in keeping up morale during this difficult period

In many respects, the performance of the 8th Hussars machine-gun troop reflected the essence of the era. Short on cash and manpower, the Hussars did what the could with what they had, in many cases with astounding results. With another world war around the corner, this training proved invaluable as Canada once again rebuilt its army